|

-- Colin Donihue PhD Candidate

I just launched a crowdfunding campaign to raise a last bit of money for my summer's research. The project is already over 70% funded! So far, the process has been an extremely exciting way to reach out to friends and strangers about my work. I hope you'll stop by to check out the video and description. I'll write another post about the whole process as the campaign is wrapping up. Thanks for your interest! Are Greek lizards adapting to live with Humans?

21 Comments

-- Colin Donihue Adam just back from stomach pumping Black Caiman (Melanosuchus niger). He'll be posting soon about his adventures, but we wanted to share this first look at just how he did it. Enjoy! And don't try this at home! -- Colin Donihue, Karin Burghardt PhD Candidates

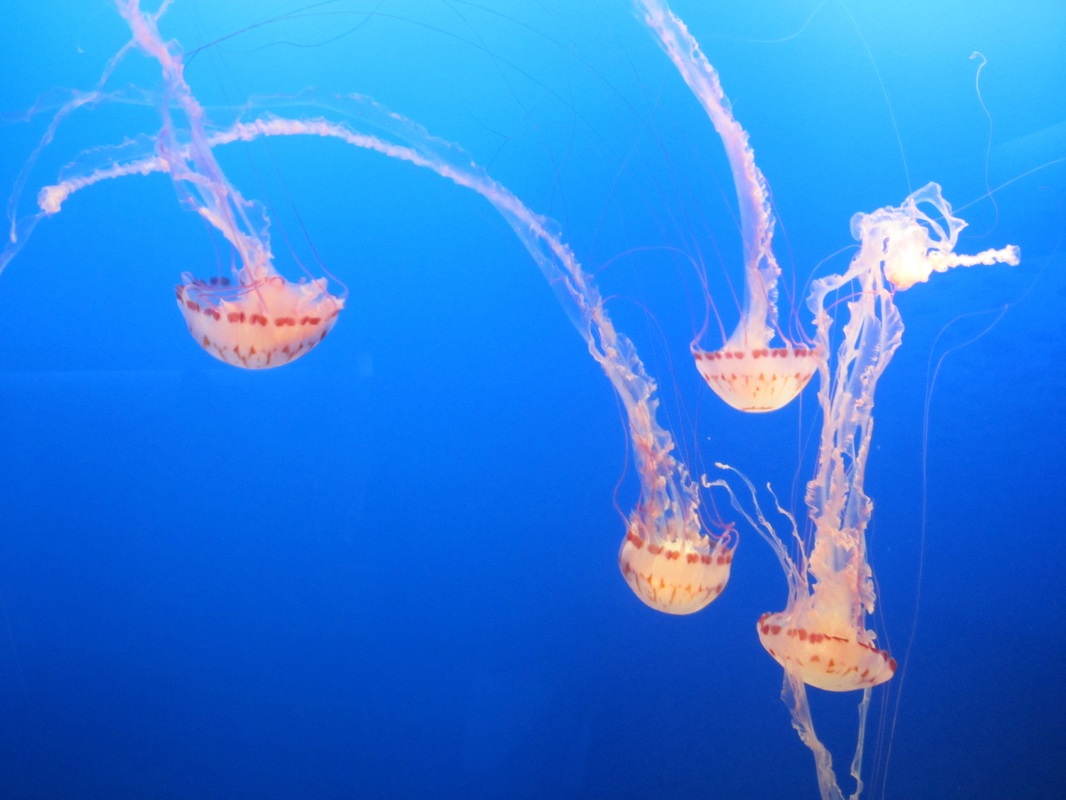

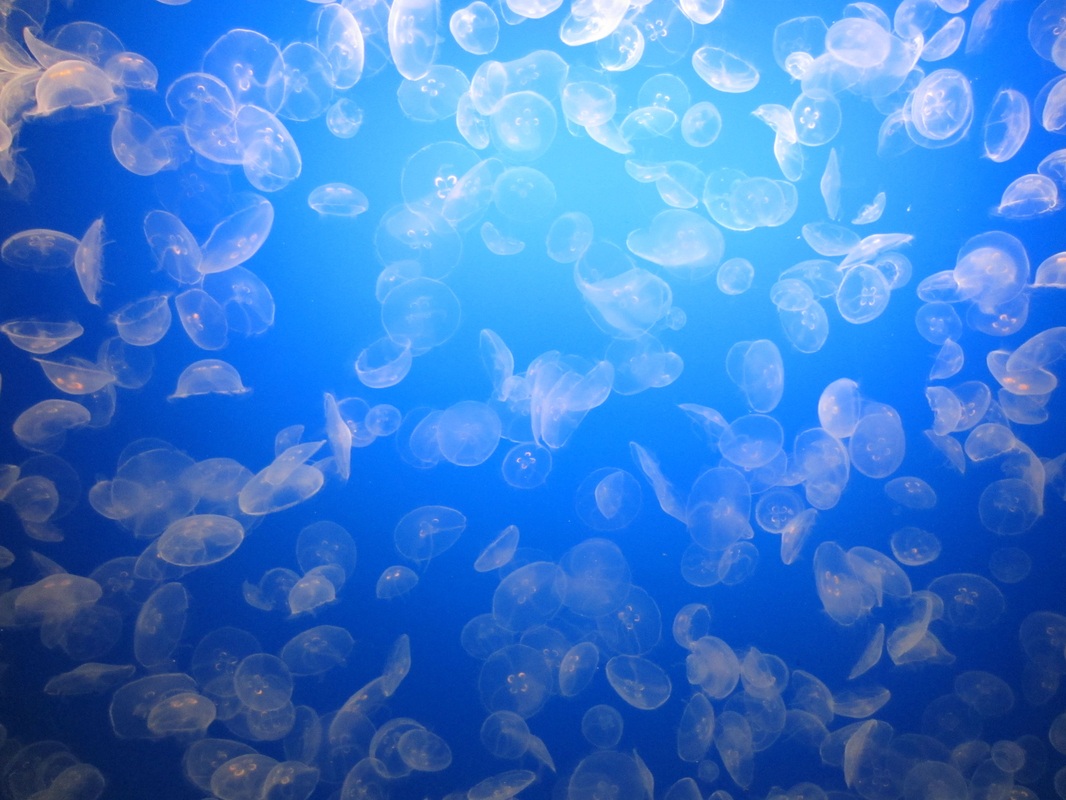

2014 has already been a big conference year for the Schmitz labbers! The week after the Predator/Prey Gordon Conference, Karin and Colin went to the American Society of Naturalists conference in Monterey. This conference aimed to "integrate pattern and process to understand biodiversity" by bringing together ecology, evolution, and behavior folks to think about some of the major questions that bridge our fields. Overall, the quality of the talks and symposia were fantastic (including a debate with lots of zombies) and we both left with great feedback on our research. Karin presented results from her greenhouse experiments on tolerance and resistance traits in goldenrod and Colin gave a quick talk about last summer's work comparing lizards from different island and human contexts. Additional highlights of the trip were the beautiful Asilomar conference grounds, the 75 degree weather, the pacific ocean tidal pools, and the Monterey Bay Aquarium. It was hard to trade sunny CA for arctic CT, but we're excited to get back to work after the stimulating conversations at the conference. Photos: The conference grounds at Asilomar, and shots from the Monterey Bay Aquarium. Credit: Karin Burghardt -- Jennie Miller, PhD Candidate

Os, Anne, Adam and I just returned from a science-packed week in sunny Ventura, California at the very first Gordon Conference on Predator-Prey Interactions. The week was jam packed with conversations with old and new colleagues, and we even reunited on the beach with Schmitz Lab alumni Andrew Beckerman, Brandon Barton and Adalbert Balog. Thanks for a great week, California! -- Kassie Urban-Mead, Undergrad A visit today to any of my thirteen research fields today won’t yield many bees, the buzzing quieted and the whirring of wings and ferrying of nectar and pollen arrested with the frost. Yet they are there—solitary bees, mated queens, a few residual workers—nestled in soil cavities, pithy stems, and deep within piles of coarse woody debris. I stole from their midst this summer over 1,400 bees as part of my senior research—I’m in pursuit of uncovering more clues as to the landscape features and human land-use practices with the strongest effects on their community integrity. Today those guys look like this: After many hours at the microscope, I had the great privilege of meeting with Sam Droege at the USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center for an identification extravaganza. Sam, a great native bee expert, worked with me for two days in his teaching lab, correcting the mis-attempts and verifying the successful determinations. He regularly brings in high school students to work on the collections, and answers phone calls from novice naturalists and seasoned conservationists, journalists, and symposium directors alike. All in a day’s work! The processing goal of the bustling lab? To increase the BPM—that is, Bees Per Minute—without losing identification, pinning, or cleanliness accuracy in the specimens. Sam found two rare bees in my collection: Calliopsis nebraskensis and Triepeolus obliteratus. Neither are unheard of in CT, but neither are there many records. The photos included here are of my C. nebraskensis specimen. The photos were taken by S. Droege with a high-powered camera; his software stitches together tens images focused at slightly different depths of field into these highly resolved images. The link to the complete photostream of arthropodal majesty is here. I feel so grateful to have been able to learn from Sam for a few days, and encourage use of his guides at discoverlife.org to novices and experts alike. With my IDs verified by Sam, I’ve moved into data analysis, and will be continuing my quest for insight into the needs of our precious native pollinators. The futures of food security, native wildflower pollination, biodiversity, and continued production of truly trippy and nigh-unto-extraterrestrial photos depend on it. Until next time! -- Katherine Mertes, PhD Candidate Guest blog post from the Jetz Lab at Yale  Understanding how animals respond to different environmental conditions is an important step in learning why a species occurs where it does. Preference for certain conditions, and aversion toward others, can explain a species’ global range – and, on a more local scale, why a species might be found only in a few specific places within its range. In order to explore such environmental preferences and distribution dynamics for East African birds, we are attaching GPS tags to multiple species. Most recently, we captured and tagged a kori bustard, one of the largest flying birds in Africa. Capturing a kori begins with conducting surveys across Mpala to identify areas where the species can consistently be found – and where Safaricom signal is strong enough to support the GSM capabilities of the sophisticated tags obtained through collaborators at the University of Konstanz, Germany. After establishing suitable areas, the capture process works like this: spot a kori during the relatively cooler morning and evening periods, as the species is particularly sensitive to heat stress. Determine the direction the kori is headed, then rush of it ahead to hang a monofilament net 3 meters tall and 50 meters long from natural vegetation, oriented perpendicular to the sun (to reduce visibility), while keeping one pair of eyes on the bird to detect any sudden changes in direction. Once the net is securely – and, hopefully, invisibly – strung from acacias, circle back and use the vehicle to carefully, steadily, slowly herd the bird into the net. If all goes smoothly, the kori unwittingly walks into the net, becoming entangled just long enough for us to emerge from the vehicle, secure the bird in a loose yet firm grip, and place a dark hood over its head to induce calm during handling. In mid-October all did go smoothly for our field team, and we successfully attached a GSM/GPS tag to an adult male kori bustard. Over the next year, precise GPS locations collected every 5-20 minutes will enable us to learn which environmental conditions these birds prefers, and just how far they will travel to track these preferred conditions. When analyzed with movement data from other tagged species at Mpala – such as red-billed and Von der Decken’s hornbills – we hope to be several steps closer to solving fundamental questions of species distribution dynamics.

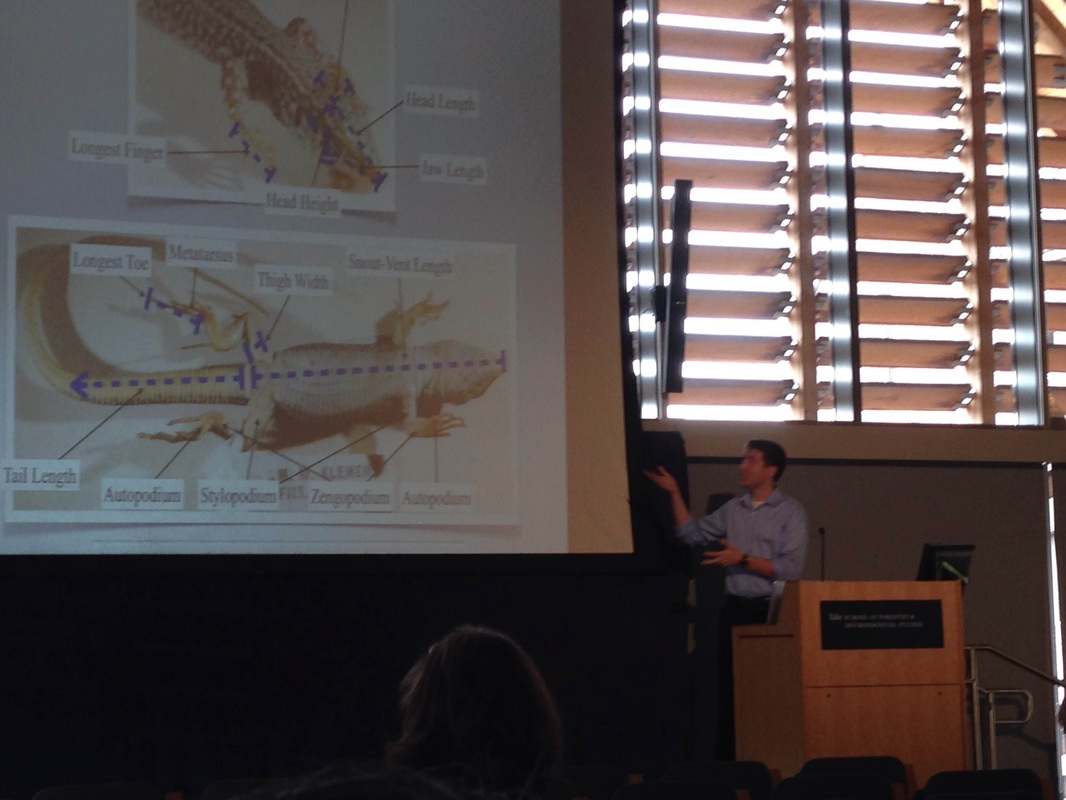

-- Colin Donihue, PhD Candidate Greece has a long history of goat grazing and stonewall building. As such, it provides an ideal setting for my studies on the effects of human land use on ecological communities. The Aegean Sea, to the south and east of Athens, is dotted with hundreds of islands, each with their own land use history and portfolio of plants and animals; these islands are my laboratory for comparative studies on the effects of wall building on local flora and fauna. In the Cyclades, my “home base” cluster of islands between Crete and mainland Greece, it is rare to see a stonewall without a lizard perched atop. Because most are built without concrete or other sealants, these walls are lizard havens, with mazes of halls and balconies perfect for escaping predators including snakes, cats, and birds of prey, or warming up in the sun. The most common lizard, and the one I’m focusing my research on, is suitably named the Aegean wall lizard, Podarcis erhardii. Given the close association of these lizards and the walls they live in, my research investigates whether lizards are changing their behavior, morphology or physiology to use these man-made structures and whether any changes that are occurring might affect other species, particularly insects and plants, in the ecosystem. This past summer I addressed these questions in two ways, testing for differences in a suite of lizard traits between islands with different ecological settings, and also testing for differences in lizards on the same island with differences in human land use. My preliminary results suggest that lizards on walls differ in behavior, morphology and performance from lizards in settings without walls. Next summer, I am designing a multi-island manipulation experiment that will involve building walls and introducing lizards to eight small islets in order to test whether these lizard trait changes are directly attributable to the stone walls, and whether these changes have cascading effects on the insects and plants of the community, as theory predicts. I spent my summer in Naxos, the largest island in the Cyclades. Naxos’ most famous feature is its ancient temple of Apollo. From Naxos, I took ferries and small fishing boats to 25 nearby islands in the Cyclades ranging in size from a football field to many miles in length; some were inhabited with fishing villages and others are wonderfully remote and human-free. Wherever I went, I was always in search of lizards. Most were too fast for hand-catching, so I used little string nooses on the end of fishing poles, or, even more successfully, small mealworms for bait. I caught, measured, and released several hundred lizards over the course of the summer. On these trips I also saw a variety of other species, including several small sand boas, many “four lined snake,” though this individual is from a unique population that mysteriously lacks lines, and lots of other critters. There is much still to learn about the roles humans play in the ecological dynamics of the Greek islands. I look forward to continue exploring this beautiful, diverse, exciting landscape. -- Colin Donihue, PhD Candidate As the old adage goes, 6 is afraid of 7, because 7 ate 9! The story might be a bit more complicated though according to Pacifica Sommers over at "Biodiversity: the Blog." Check out her recent post on predation to find out why it's 5 that 6 should be worried about!

(Thanks for mentioning our work!) (Photo Credit) -- Karin Burghardt, PhD Candidate For most people the trees losing their leaves for the year invokes a bit of sadness for the lost summer, however, I am breathing a sigh of relief. The end of the growing season and loss of leaves means a respite from fieldwork and a chance to reflect on how my experiment is shaping up (and how much more there is to be done). Last fall the lab helped me with an epic construction project to erect 28 raised beds at my field site and fill them with 20 tons of sand and 20 tons of field soil –accomplished by wheelbarrow (I know I owe them all my first born… but probably they would prefer cookies for life). In any case this past June I planted into the sandboxes mixtures of goldenrod genotypes known to express different plant defensive traits. The experiment also manipulates soil nutrients and herbivory. Over the next few years I will measure how plant defensive traits, herbivores, and nutrients influence plant and herbivore fitness and competition as well as trace nutrient cycling within the sandboxes. As a result, over the summer I spent a lot of time taking plant and nutrient measurements and playing Where’s Waldo with my grasshopper herbivores within the sandbox enclosures.

-- Kevin McLean, PhD Candidate

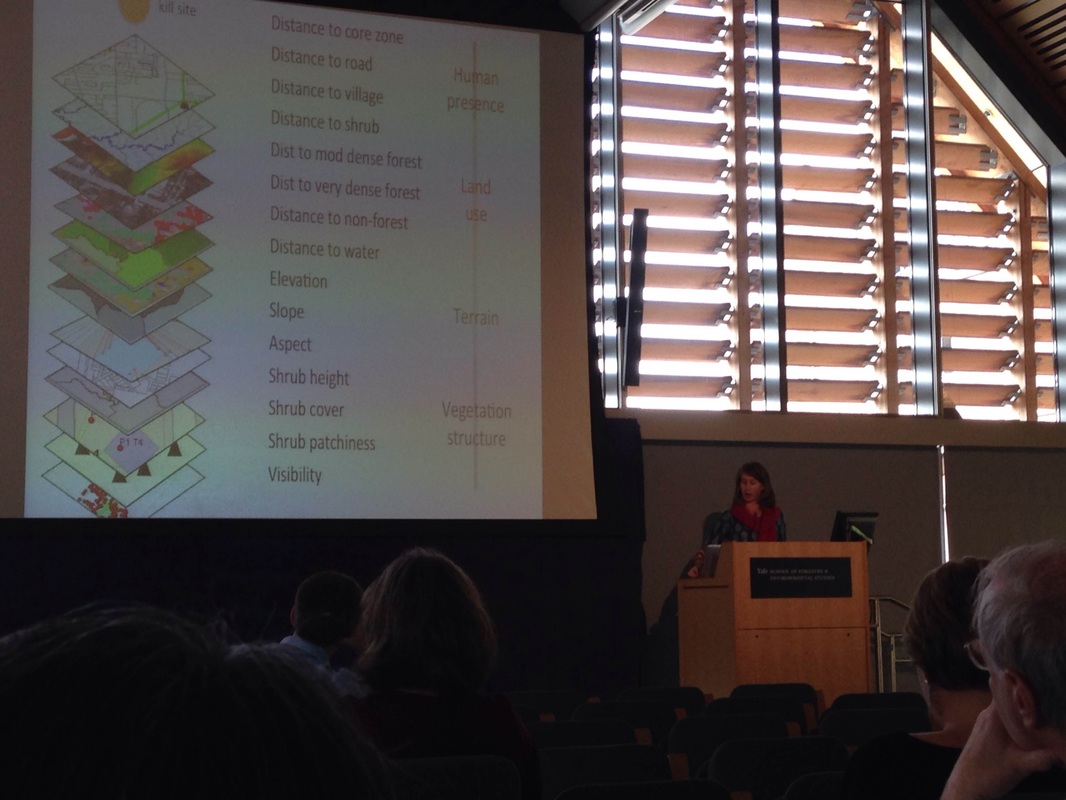

Jennie, Colin, and Kevin were among the 20 FES Ph.D. students who participated in this year's "Doc Con" on October 4. The Doc Con is the main venue for doctoral students to showcase their research to the FES and Yale community. Jennie gave a fascinating presentation about the latest findings from her predation risk modeling work (look at all those fancy map layers!). Colin, a freshly minted Ph.D. candidate, presented a selection of his preliminary results and proposed research from his qualifying examination (congrats, Colin!). Kevin spoke about the methods he used to construct his movement model and some of the (extremely) preliminary results, which he plans to test in the field this winter. The conference was very well attended, with a packed house for the keynote presentation by Peter Kareiva of The Nature Conservancy. Great job to the Schmitz Lab presenters, we're looking forward to next year's event. |

Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed