|

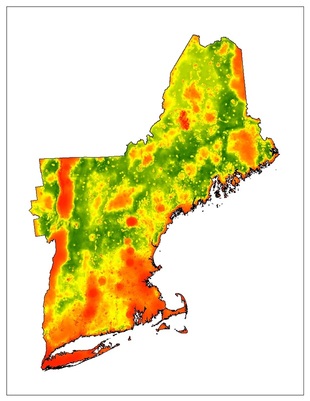

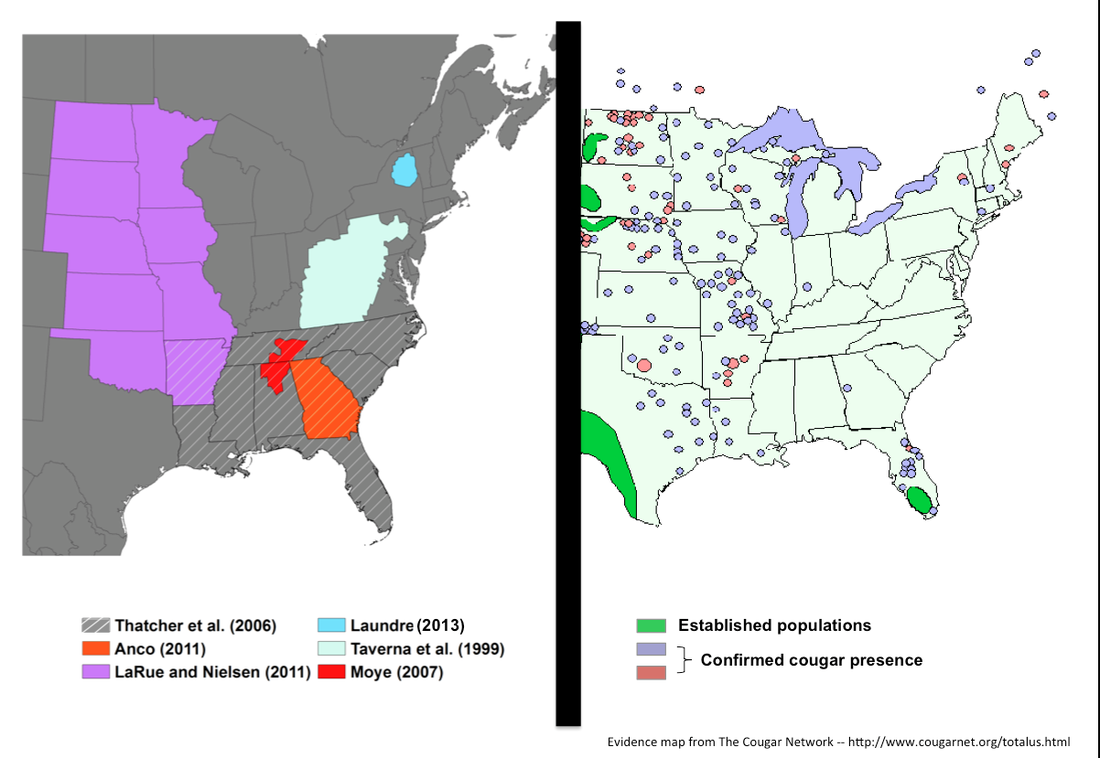

-- Henry Glick, 2012 Master's Student After several hours combing through a giant stack of reports pulled from a file box at the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife’s Field Headquarters, it was clear that hardly a month goes by without someone reporting a cougar. No, I’m not talking about a cuddly kitten or fuzzy lap cat, but a wild cougar—a mountain lion who makes its living from the land, dragging down full-grown deer with jaws that can split vertebrae. Here in the Northeast, where large carnivores have been almost entirely absent for about a century, the thought of wild cougars roaming the patchwork landscape has raised a wide range of sentiments. For many, the idea sparks curiosity or a wash of romantic nostalgia for the wildness of yesteryear. For others, this idea elicits fear—fear that an afternoon walk through the park might turn them into an extra-large serving of Fancy Feast. The stack of cougar reports is maintained by Dr. Tom French, Assistant Director of Massachusetts’ Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program and one of the region’s foremost students of cougar sightings. Compiled over many years by French and his colleagues, the stack contains records of not ten, twenty, or even fifty eyewitness accounts of cougars. No. This pile has nearly 2,000 reports scattered across the region, and they all tell the same story: cougars… cougars all over the place. This may be an exciting story, but it’s also a bizarre one considering that the in 2011 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service deemed the Eastern cougar extinct. Confusion about the presence of Puma concolor abounds. This is largely because those who have seen cougars—the believers—and those responsible for cougar management—the fish and wildlife agencies—aren’t seeing eye to eye. The believers are local residents like you or I, from all different walks of life. It has been through their observations that they have come to believe, relying on often fleeting glimpses of tawny fur to give them certainty. There’s just one problem: the regional fish and wildlife biologists, those tasked with managing the region’s natural resources (including such rare species as the cougar), have their doubts about what the believers have actually seen. The believers tell stories of terse conversations with incredulous biologists who raise their eyebrows at even the slightest mention of cougars. When authorities choose not to accept claims that four-legged eviscerators have begun to prowl the patchwork forests and suburban yards of New England, the believers become frustrated. The press feeds off this frustration, reporting believers’ claims alongside biologists’ disclaimers, while Internet message boards record unfiltered banter about the biologists’ managerial incompetence and organized deception. Fish and Wildlife agencies view their interactions with the believers from a decidedly different vantage. They assume that cougar sightings are erroneous unless proven otherwise – an approach rationalized by science and projected with an air of skepticism. Having chased down countless false reports, unless an actual animal turns up or laboratory-derived DNA points to cougars, biologists are reluctant to acknowledge the presence of the occasional animal that strays through the region, let alone a stable breeding population. The Northeast’s cougar controversy is confusing, not only because the evidence often falls within a grey zone of human interpretation, but also because the animals themselves are unpredictable. Take, for example, the first cougar carcass recovered from New England in the last 75 years, which came in 2011 after an unfortunate meeting of bumper and fur on the side of a parkway in Milford, Connecticut. As a town of 50,000 situated along the well-developed shoreline of the Long Island Sound, a mere 70 miles from the 8.2 million residents of New York City, Milford is hardly the wilderness one might have imagined. These incongruities of the cougar controversy were what first led me to Tom French’s office and ultimately to examine the Northeast’s capacity to support large carnivores. While much work has been done to examine evidence of cougars in the region—most notably a U.S. Fish and Wildlife review led by Endangered Species Biologist Mark McCollough (2011)—little has been done to evaluate cougar habitat. Researchers have used geo-spatial models to capture the defining characteristics Puma concolor habitat across the U.S. – California, South Dakota, Tennessee, Florida. However, the Northeast, which boasts the largest concentration of validated cougar evidence within the now extinct Eastern cougar’s historic range, had received little attention beyond Laundré’s (2013) efforts.  A cougar habitat distribution model in which “ideal” habitat characteristics have been derived from sites where cougars have been reported. Here, the Mahalanobis distance is used to quantify the degree of similarity between each location on the landscape and the pooled characteristics of reported locations. Dark green represents greatest similarity while dark red represents greatest dissimilarity. Habitat distribution models for generalist species like the cougar are of limited utility since there are few places these animals can’t live. However, where some information is better than no information, these models serve as valuable heuristic tools as management agencies continue to investigate dozens of eyewitness accounts each year. Through my work I found that the Northeast has, even under the most conservative of scenarios, enough habitat to support one or more small breeding populations of cougars. However, there are not, as far as we can tell, resident individuals in the region. Will there ever be? With the active expansion of cougar habitat into the Midwest, it’s likely well see more long distance dispersers in time. But while the region could support cougars from an ecological standpoint (i.e. plenty of space and plenty of food), the social carrying capacity may limit natural repopulation well into the future.

Want to learn more? Check out: Glick, H. B. 2014. Modeling cougar habitat in the Northeastern United States. Ecological Modelling, 285:78-89 [link URL: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304380014000891]

27 Comments

|

Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed