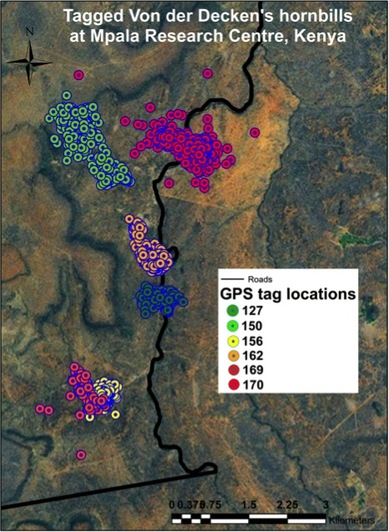

Why do species occur where they do? How do we accurately predict their occurrence? These questions have inspired naturalists and scientists for many years. Accurate species occurrence information can be used to select protected areas, identify movement corridors, and develop successful management practices. The research I conduct at Mpala Research Centre in Laikipia, Kenya investigates how environmental conditions and spatial scale influence species occurrence patterns. Both humans and animals are known to select resources at different spatial scales. For example, when choosing a city in which to live, I might consider weather patterns, local amenities, and job availability. When purchasing a home, I would want to know a house’s square footage, yard size, and safety. Animals respond to environmental conditions at different scales in similar ways. When selecting a home range, a bird might prioritize food resources, water availability, and nearby competitors. When selecting a nest site within a home range, ease of entry and shelter from predators may be more important. These habitat selection processes, combined across many individuals, determine a species’ local distribution. The first step in studying scale-dependent occurrence patterns is to measure the scales where habitat selection takes place. One method uses movements made by individuals over long time periods. Places where animals move short distances and turn in many directions likely contain important resources like food; places where animals move long distances over short time periods might be dangerous or contain less food or water. Recent technological developments make it possible for very small GPS tags (less than 20 grams) to collect a precise GPS location every 20 minutes, and run for months on solar-powered batteries. During August – October 2012, my team attached GPS tags (built by the University of Konstanz, Germany) to six adult Von der Decken’s hornbills at Mpala. One tagged hornbill often flies by the research station and dining area, showing off his GPS “backpack.” Movement data are collected by placing weatherproofed antennas, receivers, and memory units near where tagged birds roost at night (search www.movebank.org to see where tagged birds spend their time at Mpala Research Centre). After several months, we will collect enough movement data to identify important spatial scales for von Der Decken’s hornbills. Once these critical features are measured, we will build models that incorporate data on environmental conditions to understand how hornbills select habitat and resources across spatial scales. Measuring the scales that are important to different species will also help us understand how species coexist by splitting environmental resources. Together, a fuller understanding of scale dynamics and the detailed information collected by GPS tags will move us closer to understanding and predicting species occurrence patterns.

30 Comments

--Jennie Miller, PhD Candidate

Last winter in November 2011, I headed to India's Kanha Tiger Reserve to survey livestock attacked by tigers and leopards. What I discovered upon arrival shocked and compelled me: livestock die every day, yet local people are surprisingly tolerant of the large cats that kill their animals. The livestock compensation program within the boundaries of Kanha appears to be successfully abating tempers and minimizing retaliation against tigers and leopards. Three seasons, 484 dead livestock, 115 owner interviews and 152 stinky cat scat samples later, I returned to Yale in mid-October to analyze my data. To read more about my last year of fieldwork and the gist of my research, check out my guest blog on Scientists Without Borders and my just-released article in Yale's Sage Magazine. --Colin Donihue, PhD Student

Welcome to the Schmitz Lab Blog! Our lab is based at Yale's School of Forestry and Environmental Studies and, led by Dr. Oswald Schmitz, we are 2 Post-docs, 4 PhD students and 4 Masters students. Our research ranges over 4 continents from grasshoppers in the grasslands of Connecticut to tigers in the jungles of central India. We dig on our hands and knees for goldenrod rhizomes and climb 100m in emergent rainforest trees. Tying together all of these species, systems and methods is our common passion for understanding how ecological communities function and how humans affect those dynamics. More technically, Os' research focuses on plant-herbivore interactions and how they are mediated by carnivores and soil-nutrient levels, both at the level of herbivore foraging ecology and plant-herbivore population dynamics. He'll tell you more about the details in future posts, but these kinds of questions permeate all of the lab's research. We use a combination of empirical research and mathematical modeling to understand ecosystem structure and function. This blog is our effort to reach out to a broader audience to talk about our research, our interests and our perspective on scientific news and discoveries. Our weekly blog will be updated occasionally with posts from lab members on their research, pictures from the field, not-to-miss links to scientific articles and our take on them and much more, so stay tuned! We're targeting anyone with an interest in the natural world and we'd love to spark discussion, so if we're not making sense or you want more information, respond with a comment or send us an email and we'll follow up with another blog post. In addition to this blog we'll be tweeting. Follow us on Twitter for more frequent updates on the Schmitz lab. |

Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed